Thyroid disease is incredibly common. If you haven’t been diagnosed with thyroid disease yourself, you probably have at least a dozen friends and relatives who have been. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) estimates that nearly 20 million Americans have a thyroid condition. However, I believe many more people suffer from uncomfortable thyroid symptoms and it is very much under-diagnosed because of the inadequate screening labs that most practitioners use to evaluate thyroid function.

Perhaps your experience has been that you notice symptoms that seem like hypothyroidism but your doctor says over and over that your labs indicate your thyroid is working just fine. I find that the single lab marker often used to screen for thyroid issues, TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone), is usually not enough on its own to rule out thyroid issues. I believe thyroid issues are under-diagnosed because TSH alone is too often relied on to confirm thyroid issues. I will show you five reasons to help you understand this in detail through understanding thyroid physiology and the failures of conventional testing.

Understanding thyroid physiology is paramount to understanding the claims that I am making. In the previous blog, The Thyroid Part 1 – The Basics, I told you a little bit about the thyroid, where it is located, and the hormones it produces, T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine). Some of it will be recapped here, but we will also get at the root of why thyroid issues are under-diagnosed.

The Physiology

Your thyroid gland is part of your endocrine system. It regulates metabolism for every cell in your body. The word metabolism often brings to mind calories and weight gain and weight loss. Metabolism is actually something much broader- it is all the chemical reactions that occur inside cells and sustain life. Thyroid function is really important and impacts every cell of your body.

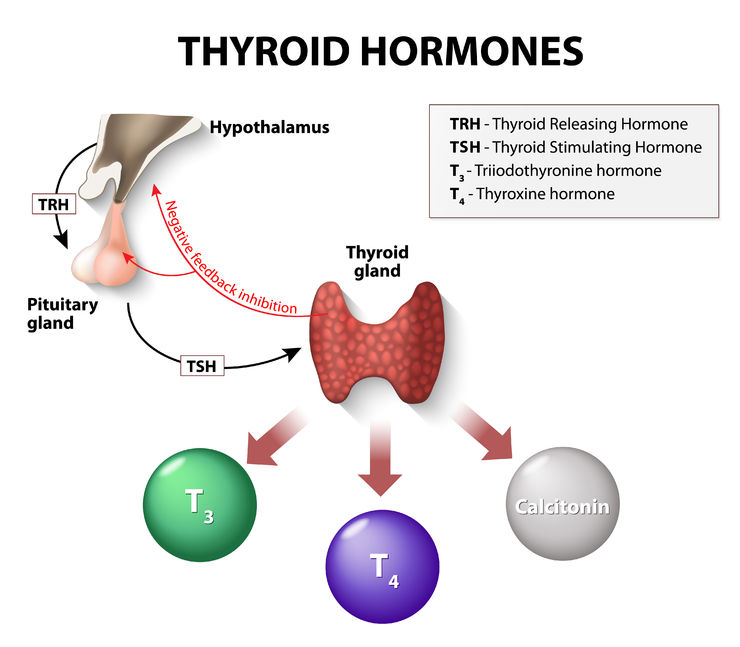

Because thyroid hormones are essential to every cell in your body, the amount of hormones your thyroid produces should go naturally up and down to respond to your body’s needs and environment. It should fluctuate according to temperature, food intake, stress, and activity level. Your hypothalamus and pituitary, glands that are located in your head and considered to be the master regulators of your endocrine system, are constantly sampling the blood for levels of thyroid hormones. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland integrate what they find in the blood with other information coming from different sources to determine whether or not your body needs more or less thyroid hormones at any given time. The levels are constantly fluctuating to respond to your environment.

Your hypothalamus gives instructions to your pituitary and your pituitary gives instructions to your thyroid. TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) is the signal your pituitary uses to communicate to your thyroid; notice that TSH is not made by your thyroid gland but is a hormone that your thyroid gland responds to. Higher TSH levels indicate that your pituitary is prompting your thyroid to produce more thyroid hormones to meet your body’s needs. Lower TSH levels mean that your pituitary is telling your thyroid to slow down production.

When your thyroid receives a signal in the form of TSH from the pituitary that your body has inadequate levels of thyroid hormone, your thyroid produces more of both T3 and T4. It actually makes just a tiny bit of T3 and a whole lot of T4. T3 is much more biologically active than T4 which means that the tissues throughout your body need to convert T4 into T3 to really be able to utilize the hormone. This is done through an enzyme that removes one molecule of iodine. T3 can then attach to receptors on your cells, go inside, and regulate cellular metabolism. It is important that your body has adequate levels of T3 and T4 in order to function optimally. Your pituitary and hypothalamus, as stated above, are constantly monitoring the blood to make sure that you do.

Conventional Thyroid Testing

TSH is measured by a blood test and is reported in milli-international units per liter (mIU/L). The sweet spot for TSH, according to many naturopathic doctors and functional medicine practitioners is about 1-2.0 mIU/L. Studies confirm that thyroid levels higher than 2.5 mlU/L are associated with obesity and the development of metabolic syndrome. (1, 2, 3)

Conventional labs suggest a normal range for TSH of about 0.4 – 4.0 mIu/L. TSH is often the only marker of thyroid function that is usually run by conventional doctors. And from what I have written so far, this might seem like it would be adequate for diagnosing thyroid issues, right? After all, the pituitary and hypothalamus are in charge of monitoring the body’s conditions and giving the thyroid instructions accordingly. But there is more to the story of thyroid physiology and many things can go wrong all along the way.

There are five underlying problems most commonly causing thyroid dysfunction.

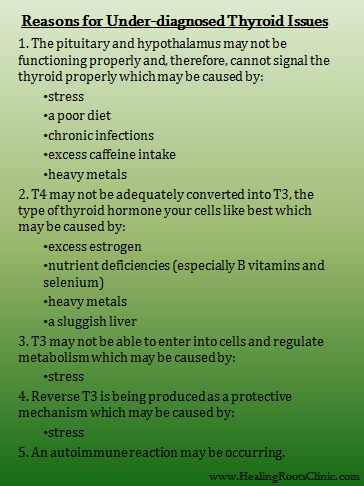

- The hypothalamus and pituitary may not be functioning properly and are not doing their job to sample the blood or signal your thyroid.

As much as we’d like to believe this, not everything in our body functions perfectly all of the time, including our hypothalamus and pituitary. These important endocrine glands are particularly susceptible to stress, both short-term acute and long-term chronic. Additionally, exposure to heavy metals (4, 5), nutrient deficiencies, diets high in refined carbohydrates, overuse of caffeine, and chronic infections can all compromise their function. This can be one of the problems of only looking at TSH as a marker of thyroid function. If TSH is the only evaluator of thyroid function, it ignores the possibility that there is dysfunction in these glands.

- The body may not be converting T4 into T3; the pituitary and hypothalamus think everything is fine because total levels of thyroid hormones are adequate.

Another potential issue is that the pituitary and hypothalamus measure both T3 and T4 and they do not discriminate between the two different thyroid hormones. Your thyroid may be making plenty of T4 but your tissues may not be converting T4 into T3. When this happens, the total T3 and T4 levels satisfy the pituitary and hypothalamus, and then TSH will not be increased even though the body needs more T3. I sometimes see Free T4 measured by conventional MDs but rarely Free T3. I find it helpful to measure both in order to get a more complete understanding of your body’s thyroid status. The “Free” refers to being unbound to a carrier protein. Carrier proteins help keep thyroid hormones ready and available in your bloodstream when needed. Bound proteins cannot be quickly used by your tissues. Measuring levels of Total T3 and Total T4 can also be useful to look at, but in many cases the Free forms are more relevant.

A typical scenario is a TSH result is within the normal range and a patient is told that her thyroid is fine… meanwhile she has symptoms of hypothyroidism because T4 can’t get into the cells and the body doesn’t have enough T3. What can block conversion of T4 to T3? Many of the issues that cause the pituitary and hypothalamus to under-function can also cause issues converting T4 into T3. Too much estrogen, a very common scenario, can also block the conversion. Selenium and select B vitamins are particularly important nutrients needed for proper conversion.

- Cells may not be letting T3 inside to do its work.

Let’s say your pituitary and hypothalamus are working fine, your thyroid is doing well and producing adequate levels of T3 and T4, and you are able to convert T4 to T3 just fine. In lab terms, TSH, Free T3 and Free T4 will all be within normal limits (see this previous article on issues with the term WNL). Your cells then need to be able to bind to T3 and bring it inside. T3 is really only useful to your cells once it is inside. High levels of cortisol, caused by chronic stress, can make it difficult for T3 to bind to receptors and get inside the cell. High toxic burden and inflammatory diets (high sugar, processed foods, too many vegetable oils, hydrogenated and rancid oils) may also cause issues for T3 as it tries to enter cells. There is solid research showing that PCBs (which are Polychlorinated biphenyls, not to be confused with BPA which is Bisphenol A found in many plastics) block thyroid receptors at the cellular level.

When patients start having a positive response (ie, they feel better!) to detoxing and anti-inflammatory diets, this supports the theory that other environmental toxins and inflammatory foods are issues as well. Toxins clog the receptors and inflammation damages the integrity of the cell membranes where the receptors are located.

- Stress can also result in the production of reverse T3 which has the wrong structure for binding to cell receptors.

Reverse T3 is another marker of thyroid status that can be measured with labs in a little more detail. Reverse T3 has an iodine molecule on backwards so that it cannot work properly in your body. This might seem like a mistake but there is wisdom in your body doing this. Reverse T3 tends to be produced when you are stressed. By making it, your body is telling you to put on the brakes and slow down; high levels of Reverse T3 is a sort of alarm your body is making to signal that things are not okay! I do not believe it is saying that you need synthetic T3 in the form of a pharmaceutical drug.

- The body may be having an autoimmune reaction to the thyroid and TSH may not be reflecting this… yet.

Most commonly autoimmunity is behind the majority of cases of hypothyroidism. An autoimmune reaction can be occurring for a very long time before it is reflected in a high TSH value. From a naturopathic perspective, it is important to catch the imbalance before too much tissue destruction has occurred. The conventional thinking is that if autoimmunity is an issue, your thyroid will eventually be subject to enough destruction due to your body’s production of antibodies against its own tissue that TSH levels will elevate. So, they look for elevated TSH and not necessarily antibodies. They then address the issue by giving thyroid hormone (in the case of autoimmune hypothyroidism/Hashimoto’s) or your thyroid being surgically removed (in the case of autoimmune hyperthyroidism/Grave’s Disease).

Clinical experience tells me that waiting until TSH reflects damage to your thyroid before considering an autoimmune cause of thyroid disease is, at the very least, not a very good idea or thorough approach. Sometimes it is downright dangerous and the missing piece of knowledge prevents underlying issues from being addressed while they are still manageable. I have seen staggeringly high antibodies with normal TSH levels. Twice in a 3-week span I ran full thyroid panels on two young women who had been told they had normal thyroids by other doctors. Both had antibody levels of 1,000+ which reflected a serious immune reaction causing them both to feel terrible with a “normal” TSH result.

Full Thyroid Panel

To accurately test the thyroid, I recommend my patients have these tests drawn at the very least:

- TSH

- Free T3

- Free T4

- Thyroid Antibodies (Anti-TG and Anti-TPO)

Additionally, adding the tests for Total T3, Total T4, and Reverse T3 will ensure that we get the most accurate picture possible to determine the actual reason behind symptoms.

To find out why taking thyroid medicine can be, and often is, over-medicating and not addressing the real cause, check out The Thyroid Part 3 – Do I Have to Stay on Thyroid Medication for My Whole Life?

My mother has been suffering from hypothyroidism and I’m really worried about her. Also, Your blog contains great information.